The Bernese Mountain Dog in the United States: Historical Development, Population Genetics, and Implications for Contemporary Breeding

Abstract

The Bernese Mountain Dog (BMD) in the United States represents a compelling case study in founder effects, genetic bottlenecks, and the tension between numerical population growth and effective population size. This paper synthesizes historical, demographic, and genetic evidence to examine how the breed was established in the U.S., how its genetic structure has evolved, and how these dynamics have shaped contemporary health challenges—particularly cancer, orthopedic disease, and inbreeding depression. We further explore how modern breeding strategies, including outcrossing with Australian Shepherds, may mitigate some of these risks while introducing new responsibilities for long-term monitoring and transparency. The analysis underscores that ethical stewardship of the breed requires both rigorous health screening and intentional management of genetic diversity.

Executive Summary

This white paper provides a comprehensive analysis of the Bernese Mountain Dog's establishment and evolution in the United States, offering critical insights for breeders dedicated to genetic health and responsible stewardship. By examining the breed’s history—from its 1926 importation to its current status—we uncover valuable lessons regarding founder effects and population dynamics.

Key findings highlight a stark reality: despite a rising population census, the breed suffers from restricted genetic diversity due to "popular sire" effects, where less than 1% of sires have historically produced over half the next generation. This bottleneck has contributed to significant health burdens, most notably a cancer mortality rate of 67%, with Histiocytic Sarcoma affecting approximately 25% of the population.

However, there is a path forward. This report outlines actionable breeding strategies, including the use of vertical pedigrees, transparent health data reporting, and the careful management of outcrossing to reduce inbreeding depression. For the conscientious breeder, understanding these dynamics is not just about preserving the past—it’s about ensuring a healthy, joyful future for every puppy that comes into our care.

Introduction

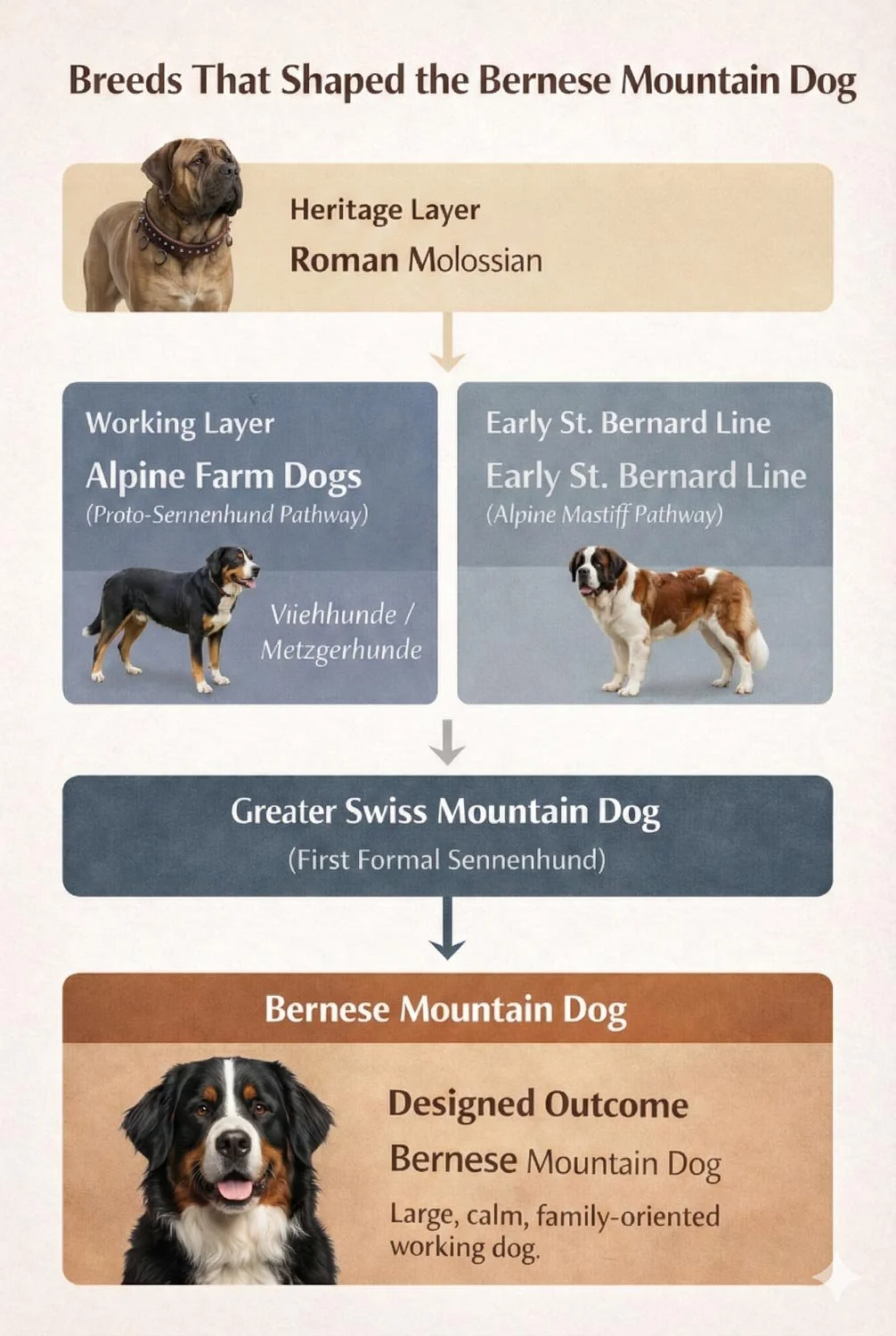

The Bernese Legacy: Briefly trace the breed's journey from Roman Mastiff descendants in the Swiss Alps to their role as "Sennenhund" (dairy farmer's dog), emphasizing their dual purpose as working dogs and devoted family companions.

The U.S. Context: Introduce the specific focus of the paper: the development of the breed in the American landscape, characterized by a small initial gene pool and rapid popularity growth.

Objective: Define the goal of this white paper—to equip breeders with high-level knowledge on genetic constraints, health risks, and modern breeding protocols to improve longevity and vitality in future generations.

Purebred dog populations provide a unique natural experiment in population genetics. Unlike most species, they have been shaped by human-mediated selection, closed stud books, and intense reproductive skew. The Bernese Mountain Dog in the United States exemplifies these dynamics. Despite growing in popularity and numerical representation over the past century, the breed continues to exhibit high genomic relatedness, elevated cancer prevalence, and persistent orthopedic disease risk.

This paper addresses three central questions:

How did the Bernese Mountain Dog become established in the United States, and what demographic forces shaped its early gene pool?

What do contemporary genetic analyses reveal about inbreeding, effective population size, and disease burden in the breed?

How might modern breeding strategies—particularly F1 outcrosses—alter these trajectories, and what safeguards are necessary to ensure responsible genetic stewardship?

Comprehensive History of the Bernese Mountain Dog

Origins and Early Development of the Greater Swiss Mountain Dog (GSMD)

The Greater Swiss Mountain Dog (GSMD) is widely regarded as the oldest of the four Swiss Sennenhund breeds and is believed to have played a foundational role in the development of other large working breeds, including the St. Bernard and the Rottweiler. The precise ancient origins of the Sennenhund remain debated, but three primary theories dominate scholarly discussion. The most widely accepted hypothesis suggests descent from Roman Molossian dogs — large, mastiff-type working animals brought into the Alpine regions during the Roman incursions of the 1st century BCE. A second theory proposes that Phoenician traders introduced large working dogs into the Iberian Peninsula around 1100 BCE, which later migrated eastward and influenced the development of Mediterranean and Alpine mastiff-type breeds, including the Spanish Mastiff, Great Pyrenees, Dogue de Bordeaux, and ultimately the Swiss Sennenhund. A third perspective posits that a large, indigenous working dog may have already existed in central Europe during the Neolithic period, later interbreeding with Roman Molossian stock. Regardless of their exact origin, it is broadly accepted that Roman Molossian-type dogs contributed significantly to the genetic foundation of the Greater Swiss Mountain Dog, the St. Bernard, and the Bernese Mountain Dog.

Early Functional Breeding in Central Europe

Prior to formal breed standardization, early Swissy ancestors were primarily shaped by function rather than phenotype. Farmers, herdsmen, and merchants selectively bred dogs for practical roles such as guarding, cart-pulling, and livestock management. These dogs were commonly referred to as Viehhunde (“cattle dogs”) or Metzgerhunde (“Butcher’s Dogs”), reflecting their occupational utility rather than a defined breed identity. By the 19th century, these large, muscular working dogs — often displaying tri-color, red-and-white, or black-and-tan patterns — were once among the most common dogs in Switzerland. However, by 1900, their numbers had sharply declined, largely due to industrialization and the rise of mechanized transport, which reduced the need for draft and working dogs.

"Viehhunde" and "Metzgerhunde" are general German terms describing working dogs based on their function, not specific breed names. They are historically significant as the types of farm dogs from which breeds like the Bernese Mountain Dog evolved.

Viehhunde ("Cattle Dogs"): This is a general term for dogs used to herding, driving, and guarding cattle. The dogs that became the Swiss mountain breeds were essentially local types of Viehhunde found on farms in the alpine regions.

Metzgerhunde ("Butcher's Dogs"): This term refers to strong, robust dogs used by butchers and cattle dealers. Their primary roles were:

Droving: Driving cattle to market for slaughter.

Cart Pulling: Pulling carts laden with meat.

Protection: Guarding the butcher's money pouch on the journey home from market.

Historically, the ancestors of the Swiss mountain dogs often fulfilled both roles. A farmer's "Viehhund" might also serve as a "Metzgerhund" when it was time to take livestock or produce to market. The terms describe the dog's job rather than its specific pedigree. As breeds became standardized in the early 20th century, these general functional types were refined into the distinct breeds we know today.

Sennenhund: The Swiss Mountain Farm Dogs

The term Sennenhund refers to a family of four historic Swiss mountain dog breeds—the Bernese Mountain Dog, Greater Swiss Mountain Dog, Appenzeller, and Entlebucher. Rooted in the alpine traditions of Switzerland, these dogs were originally bred and shaped by the Senn—the dairy herdsmen and farmers of the Swiss Alps. Translated from German, Sennenhund means “dog of the Senn,” a name that reflects their centuries-long role as loyal, intelligent, and hardworking farm companions.

Developed in the rugged mountain landscapes of Switzerland, the Sennenhund breeds were indispensable to rural life. They guarded livestock from predators, assisted with herding, protected family homesteads, and pulled carts loaded with milk, cheese, and supplies. More than just working dogs, they were deeply integrated into the rhythm of alpine farm life—steady, capable, and reliable in demanding conditions.

Visually, all four Sennenhund breeds are united by their striking tri-color coat—typically black, rust or tan, and white—a pattern that has become a hallmark of the group. While they share this signature look, each breed developed unique characteristics suited to its specific working role.

The Four Sennenhund Breeds

Bernese Mountain Dog (Berner Sennenhund): The most widely recognized of the four, the Bernese is large, gentle, and distinguished by its long, silky coat. Today, it is beloved as both a family companion and a versatile working dog.

Greater Swiss Mountain Dog (Grosser Schweizer Sennenhund): The largest and oldest of the group, this breed is powerfully built with a short, dense coat. Historically, the Greater Swiss was a premier draft and farm dog, prized for its strength and endurance.

Appenzeller Sennenhund: Medium-sized and full of energy, the Appenzeller is highly alert, vocal, and agile—traits that made it an excellent cattle dog in steep alpine terrain.

Entlebucher Mountain Dog (Entlebucher Sennenhund): The smallest of the four, the Entlebucher is quick, athletic, and highly driven, excelling at herding and all-around farm work.

Across all four breeds, the Sennenhund temperament is defined by intelligence, faithfulness, and dependability. Whether working in the pastures of Switzerland or serving as devoted companions today, these dogs embody a legacy of strength, loyalty, and deep partnership with the families who shaped them.

Albert Heim and the Formal Recognition of the Breed

A pivotal moment in the formalization of the Sennenhund breeds occurred at the 1908 jubilee dog show marking the 25th anniversary of the Schweizerische Kynologische Gesellschaft (SKG, Swiss Kennel Club). Two dogs were entered as “short-haired Bernese Mountain Dogs,” but Professor Albert Heim — a prominent Swiss canine researcher and advocate for indigenous breeds — recognized them as representatives of a distinct large Sennenhund type. Heim’s advocacy led to the formal recognition of the Grosser Schweizer Sennenhund (Greater Swiss Mountain Dog), which was subsequently entered into the Swiss Stud Book in 1909.

From Dürrbach Farm Dog to “Designed” Bernese: How a Breed Was Actually Made

The dog we now call the Bernese Mountain Dog did not emerge as a fully formed “purebred” animal — it was shaped, selected, and ultimately designed through a combination of rural working traditions, early dog-show culture, and a series of pivotal human decisions in the first decades of the 20th century.

Historically, these dogs were known locally as Dürrbächler (or Dürrbach dogs), named after the Dürrbach region near Riggisberg in the Canton of Berne, where a remarkably consistent type of large, tri-colored farm dog had been preserved among working families. Long before formal breed standards existed, these dogs served as true multipurpose Alpine farm dogs — guarding property, assisting with cattle, and, importantly, pulling carts for milkmen and tradesmen (the “Küherhunde,” or cowherds’ dogs). Contrary to later claims that the breed was nearly extinct by the early 1900s, a 1910 gathering in Burgdorf attracted 107 local dogs, of which 99 were judged to be true Dürrbächler type — suggesting that the dogs had remained common in the countryside even as they were underrepresented in early dog shows (Bärtschi, 2006/2011).

The formalization of the breed began in earnest in 1907, when a group of Burgdorf merchants and dog fanciers — including Gottfried Mumenthaler, Max Schafroth, and Dr. Scheidegger — founded the Schweizerischer Dürrbachclub. These men established the first foundation kennels (“zur Gysnau,” “von Burgdorf,” “vom Burigut,” and others) and began coordinated breeding efforts. Their work coincided with the growing influence of the Schweizerische Kynologische Gesellschaft (SKG/SCS), the Swiss Kennel Club, which had been standardizing breeds since the 1880s and maintaining the Swiss Studbook (SHSB) (Bärtschi, 2006/2011).

A turning point came at the 1908 Langenthal Jubilee Show, where Professor Albert Heim, the leading authority on Swiss Sennenhund breeds, made a decision that literally split one working population into two modern breeds. When confronted with short-coated Dürrbächler males (Bello and Nero), Heim ruled that they did not belong with the long-coated dogs and instead registered them as the first Greater Swiss Mountain Dogs in the SHSB. From that moment forward, coat length became a defining boundary: long coat for Bernese, short coat for Greater Swiss — a clear example of how expert judgment, not natural biology, structured breed identity (Bärtschi, 2006/2011).

Equally revealing was the early controversy over the breed’s name. While the SKG favored Berner Sennenhund, the Burgdorf club insisted on Dürrbachhund, arguing that “Sennenhund” reflected eastern Swiss language and culture rather than Bernese rural tradition. For decades, both names were used in parallel, and even today older locals still refer to Bernese as “Dürrbächler” — a reminder that breeds are as much cultural constructs as biological ones (Bärtschi, 2006/2011).

Perhaps most importantly for understanding modern genetics, early registration was loose: until 1930, dogs of “breed type” with unknown parentage could still be entered into the studbook. Only after 1930 did Switzerland fully close the registry to dogs without registered parents — a move that, while stabilizing appearance, also narrowed the gene pool that defines today’s Bernese Mountain Dog (Bärtschi, 2006/2011).

From countryside to standard, and from few to many, the Bernese Mountain Dog’s story is one of intentional selection shaping lasting outcomes. While the Swiss Kennel Club had existed since 1883, 1912 marked a turning point when the Dürrbach Club formally embraced the name Berner Sennenhund, uniting local breeders with the national standard.

Though 107 Dürrbächler-type dogs were gathered in Burgdorf in 1910, this was evidence of a living working population — not the breed’s genetic foundation. The Bernese we know today emerged from a far smaller, carefully chosen group of dogs refined between 1907 and 1930 through the Swiss studbook. When the breed later arrived in America in the late 1960s and 1970s, it came through only a handful of European lines, leaving modern U.S. Bernese largely shaped by just four to ten influential ancestors.

At Stokeshire, we honor this history by designing forward — protecting diversity, resisting bottlenecks, and breeding with intention so heritage becomes health, not limitation.

Taken together, this history makes one point unmistakably clear: the Bernese Mountain Dog is not simply a relic of the past — it is the product of deliberate human choices about aesthetics, identity, and function. In other words, the breed we know today was designed long before modern genetics ever entered the conversation.

20th Century Development and Establishment in the United States

Throughout the early 20th century, the GSMD population in Europe grew slowly and remained relatively rare. During World War II, the Swiss Army utilized the breed as a draft dog, and by 1945, the total population was estimated at approximately 350–400 individuals — effectively a severe genetic bottleneck. The breed was introduced to the United States in 1968 when J. Frederick and Patricia Hoffman, with assistance from Perrin G. Rademacher, imported the first Swissys. This led to the formation of the Greater Swiss Mountain Dog Club of America (GSMDCA), supported by Howard and Gretel Summons, which emphasized careful, selective breeding to rebuild population numbers while preserving working temperament and structural soundness. The first GSMDCA National Specialty was held in 1983, with a registry of 257 dogs. The breed entered the AKC Miscellaneous Group in 1985 and achieved full recognition in the AKC Working Group in July 1995.

Figure X. Simplified historical model of the breeds and lineages contributing to the Bernese Mountain Dog. Ancient Roman Molossian dogs likely influenced early Alpine working dogs, which evolved into the Sennenhund farm-dog complex. The Greater Swiss Mountain Dog served as a structural and functional template for later large Sennenhund breeds, including the modern Bernese Mountain Dog.

Origins and Establishment of the Bernese Mountain Dog in the United States

Early Imports and Founder Construction (1926–1937)

The first documented U.S. importation of Bernese Mountain Dogs occurred in January 1926, when Isaac Schiess of Florence, Kansas, imported Donna von der Rothöhe and Poincaré von Sumiswald. Although Schiess attempted to register these dogs with the American Kennel Club (AKC), the breed was not yet recognized, necessitating registration through the Swiss Kennel Club for their 1926 litter.

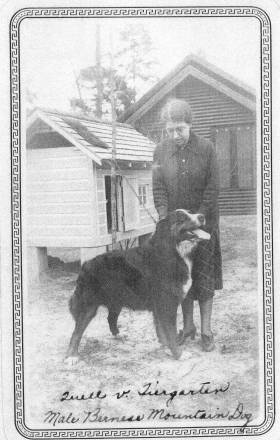

QUELL V TIERGARTEN

FRIDY V HASLENBACH

Stokeshire Research Brief

Bernese Mountain Dog Milestones in the United States

A concise historical timeline (imports → recognition → institutions → genetics infrastructure).

A second, more consequential importation occurred in 1936 when Glen L. Shadow of Ruston, Louisiana, acquired Fridy v. Haslenbach and Quell v. Tiergarten (“Felix”). These dogs became foundational to the breed’s formal recognition in the U.S.

On April 13, 1937, the AKC officially recognized the Bernese Mountain Dog as part of the Working Group, and by June of that year, Fridy and Felix became the first AKC-registered Bernese Mountain Dogs in the United States.

1926: Isaac Schliess — first Bernese imported to the U.S. (isolated import).

1936: Glenn Shadow imports Felix and Fridy to Louisiana (early but not yet sustainable U.S. population).

1988: Bernese Mountain Dog officially recognized by the AKC and placed in the Working Group.

Early Population Bottleneck

For over a decade following AKC recognition, Glen Shadow was the sole breeder of AKC-registered Bernese Mountain Dogs in the U.S. This period represents an extreme genetic bottleneck, wherein a single breeder and a very small number of foundation dogs shaped the entire early American population.

Such conditions are classically associated with:

Reduced genetic diversity

Increased coancestry

Elevated risk of recessive disease expression

Long-term vulnerability to inbreeding depression

Institutional Development (1968–1995)

The formation of the Bernese Mountain Dog Club of America (BMDCA) in 1968 marked a turning point in breed governance, standardization, and health monitoring. The club gained AKC member status in 1981, ushering in an era of coordinated national breeding practices, specialty shows, and data collection.

In 1995, the establishment of the Berner-Garde Foundation further advanced open-access pedigree and health databases, laying the groundwork for more transparent genetic management.

Population Growth and Demographic Shifts

Between 1968 and 1985, AKC registrations increased from 43 to 683 annually, signaling a rapid expansion from niche rarity to mainstream recognition. By the late 2000s, annual registrations exceeded 3,000, and the breed’s AKC popularity ranking climbed from #49 in 2000 to #38 in 2010.

However, numerical growth did not equate to genetic robustness. A critical distinction must be made between census population size (Nc) and effective population size (Ne). While Nc grew substantially, Ne remained constrained due to concentrated breeding among a small subset of popular sires.

Historical Establishment & Population Dynamics

Early Importation (1926-1937):

Detail the arrival of the first import pair, Donna von der Rothöhe and Poincaré von Sumiswald, in Kansas (1926).

Discuss the pivotal role of Glen L. Shadow and his imports, Fridy v. Haslenbach and Quell v. Tiergarten, leading to AKC recognition in 1937.

The "Founder Bottleneck": Explain the genetic implications of the breed’s early years, where for over a decade, the U.S. population relied essentially on a single owner-breeder.

Institutional Growth: Highlight the formation of the Bernese Mountain Dog Club of America (BMDCA) in 1968 and the transition from a rare breed to a nationally distributed population (ranking #38 in popularity by 2010).

Genetic Structure & The Diversity Challenge

Census vs. Effective Population: Clarify the difference between the total number of dogs (census) and the genetic diversity available for breeding (effective population size).

The "Popular Sire" Effect: Present data showing extreme reproductive skewness, where ~0.78% of sires have historically produced over 50% of the next generation, accelerating the loss of diversity.

Understanding COI (Coefficient of Inbreeding):

Pedigree vs. Genomic Data: Contrast pedigree-based COI (often underestimating relatedness due to missing ancestors) with genomic measures like Runs of Homozygosity (ROH).

The Reality of "High Relatedness": Cite studies showing mean genomic inbreeding coefficients of ~0.395, indicating that short pedigrees often mask the true extent of genetic closeness.

Estimated Founder Contributors

Rough global estimate:

10–30 core ancestral individuals

This is not a registry headcount — it’s a genetic interpretation of how many distinct ancestors today’s gene pool descends from.

And in the U.S. specifically, the number is even smaller — probably <10 impactful ancestors in the early decades.

Why This Matters (Genetically) for Bernese

Because so many modern Bernese share a narrow ancestor set:

Genetic diversity is reduced relative to a truly large breeding pool.

Popular sire effects accelerate relatedness.

Complex diseases like histiocytic sarcoma, cancer susceptibility, and joint disease have higher prevalence because deleterious alleles can become more widespread when there's limited founder diversity.

This is why:

COI values even in deep pedigrees are moderate but misleadingly low, because pedigree records are incomplete.

Genomic inbreeding (from ROH) is much higher than pedigree COI suggests.

Breed clubs and genomic researchers emphasize diversity management, outcrossing strategies (like your Australian Mountain Dog work), and avoiding overconcentration of a few sires.

Although hundreds of thousands of Bernese Mountain Dogs are now registered worldwide, all modern Bernese ultimately descend from a remarkably small number of original ancestors, meaning that the breed is far less genetically diverse than its large population size suggests. In the United States, the foundational population effectively traces back to fewer than 10 truly influential dogs imported in the 1920s and 1930s, while globally the effective founder number — the count of distinct ancestors that meaningfully contributed unique genetic material to today’s gene pool — is likely no more than 10–30 dogs. This distinction is critical to understanding what “purebred” actually means: it does not mean genetically diverse, but rather genetically closed, standardized, and increasingly related over time. Once a breed is formalized, stud books are closed, and breeding occurs only within that population, relatedness steadily increases with each generation, especially when a small number of popular sires dominate reproduction. As a result, even though there are now hundreds of thousands of registered Bernese, they are all variations on a very narrow ancestral template, sharing a high degree of genetic similarity, longer runs of homozygosity, and elevated risk for certain inherited diseases. In this sense, “purebred” reflects lineage consistency and predictability, not genetic breadth — which is why managing diversity, limiting popular sire use, and thoughtfully incorporating outcross strategies are so important for the long-term health of the breed.

The Health Landscape: Cancer & Complex Traits

The Cancer Burden: Address the statistic that 67% of breed deaths are attributed to cancer.

Histiocytic Sarcoma (HS):

Define HS as a breed-enriched, aggressive cancer affecting ~25% of the population.

Explain the genetic complexity of HS (polygenic/oligogenic), noting that it involves multiple risk loci (e.g., on chromosome 11) rather than a single "bad gene."

Orthopedic & Neurological Concerns:

Dysplasia: Review prevalence rates for hip dysplasia (~14%) and elbow abnormalities (~24.5%).

Degenerative Myelopathy (DM): Discuss the presence of two distinct SOD1 mutations and the necessity of DNA testing to manage risk.

Breeding Implications & Strategic Interventions

Moving Beyond "Single-Gene" Thinking: Argue for a holistic approach to breeding that balances specific trait selection with the preservation of genome-wide diversity.

The "Vertical Pedigree" Approach: Advocate for analyzing health trends across siblings, parents, and grandparents—not just the individual dog—to predict risks for complex diseases like cancer.

Outcrossing Case Study

Analyze the "Australian Mountain Dog" (F1 cross) example.

Benefits: Documented reduction in inbreeding depression and lower probability of recessive disease expression.

Residual Risks: Caution that polygenic traits (like cancer liability) and structural issues are not instantly eliminated and require continued, rigorous screening.

Stokeshire Genetics Visual

Why Genetic Diversity Can Shrink Even as Registrations Rise

In Bernese pedigree analysis, reproduction is highly concentrated: ~5.5% of males are used, and ~0.78% of sires account for over half of the next generation. (Illustrative visuals based on these anchors.)

Pareto-Style Skew (Illustrative)

Cumulative % of offspring vs. cumulative % of sires. Anchored at: 0.78% → 50% and 5.5% → 100%.

"100 Males" Intuition Graphic

If you had 100 male dogs available, only about 6 are used for reproduction (~5.5%), and fewer than 1 out of 100 sires can account for >50% of the next generation (~0.78%).

Animated "Gene Pool Narrowing" Funnel

Even with a large registry, effective genetic contribution can funnel through a small number of sires— accelerating diversity loss and amplifying risk alleles over time.

Design note: this is a conceptual visualization of contribution concentration, not a full population simulation.

Best Practices for the Modern Breeder

Data Transparency: Emphasize the importance of open reporting for all health outcomes, including accurate death dates and cause-of-death data, to benefit the broader community.

Recommended Screening Framework:

Structural: Hip and Elbow evaluations (OFA/PennHIP).

Clinical: Eye (ophthalmologist) and Heart (cardiologist) exams.

Genetic: DM status (both alleles) and participation in biobanking for research.

Mate Selection Strategy: Prioritize matings that maintain or reduce COI relative to the breed average and utilize tools like Berner-Garde to assess pedigree depth.

Genetic Structure, Diversity, and Inbreeding

Founder Effects and Popular Sire Dynamics

Pedigree analyses reveal that Bernese Mountain Dogs exhibit classic signatures of restricted genetic diversity. A large French pedigree study demonstrated that only 5.5% of males were used for reproduction per generation, and fewer than 1% of sires produced more than half of the next generation. This extreme reproductive skew accelerates the loss of genetic diversity and amplifies disease-associated alleles.

Coefficient of Inbreeding (COI): Pedigree vs. Genomic Measures

Inbreeding can be quantified via:

Pedigree-based COI (Wright’s F)

Runs of Homozygosity (ROH) from genomic sequencing

Pedigree-based estimates vary dramatically depending on depth:

Whole-pedigree F ≈ 0.197 (19.7%)

10-generation COI ≈ 6.1%

5-generation COI ≈ 2.2%

By contrast, genomic ROH-based estimates suggest a mean inbreeding coefficient of approximately 0.395 (39.5%), indicating that short pedigrees significantly underestimate true genetic relatedness.

Berner-Garde Base Year COI Method

Berner-Garde calculates COI using a base year of 1966, incorporating all ancestors born after that date. This standardizes comparisons across matings but depends heavily on complete whelp-date records.

Breed-average COI under this method ranges from 5.3% to 6.6%, depending on pedigree completeness.

Reduction of Coefficient of Inbreeding (COI) Through Intentional Outcrossing

Measured genetic diversity is not a marketing claim—it's population mathematics. This analysis demonstrates how strategic crossbreeding with genetically unrelated breeds immediately reduces inbreeding coefficients in F1 offspring.

Health Trends and Disease Burden

Cancer and Histiocytic Sarcoma (HS)

Cancer is the leading cause of death in Bernese Mountain Dogs. The BMDCA’s 2005 health survey reported that 67% of deceased dogs died from cancer, with histiocytic sarcoma disproportionately represented (often cited at ~25% prevalence).

Genomic studies identify multiple risk loci on canine chromosome 11 (CFA11), implicating complex polygenic inheritance rather than single-gene causation.

Orthopedic Disease

Hip and elbow dysplasia remain prevalent concerns:

Hip dysplasia: ~14% among evaluated dogs

Elbow abnormalities: ~24.5%

These findings underscore the need for rigorous screening via OFA, PennHIP, or equivalent systems.

Degenerative Myelopathy (DM)

Bernese Mountain Dogs carry two distinct SOD1 mutations associated with DM, making comprehensive DNA screening (SOD1A and SOD1B) essential.

Breeding Practices and Genetic Stewardship

Avoiding Genetic Shrinkage

The greatest risk to the breed is not individual inbreeding events but cumulative diversity loss due to repeated use of popular sires. Responsible breeding requires:

Broadening sire usage

Encouraging international gene flow

Maintaining transparent, multi-generational health records

Recommended Testing Framework (BMDCA/CHIC)

Minimum recommended screening includes:

Hips and elbows

Cardiac evaluation

Ophthalmologic exam

DM DNA testing (SOD1A & SOD1B)

Optional testing may include vWD, thyroid panels, or HS risk screening.

Case Study: F1 Australian Mountain Dogs

Genetic Rationale

The Berese x Aussie pairing represents an F1 cross between an Australian Shepherd and a Bernese Mountain Dog. This approach:

Dramatically reduces within-breed inbreeding

Increases heterozygosity

Lowers the risk of recessive disease expression

Berner-Garde analyses suggest that each 1% increase in COI correlates with approximately a three-week reduction in lifespan in Bernese, reinforcing the potential benefits of outcrossing.

Residual Risks

Despite the benefits, F1 crosses do not eliminate:

Polygenic cancer risk

Orthopedic vulnerability

Potential DM carrier status

Ulli the Bernese Mountain Dog Wins Best in Show at the 2024 AKC National Owner-Handled Series Finals

In a moment that will be remembered as a milestone for the breed, GCHG CH Windfall Adesa 3 Wire Winter @ Emerald Mtn CD RN FDC CGC — known affectionately as “Ulli” — claimed Best in Show at the 2024 AKC® National Owner-Handled Series (NOHS) Finals.

The prestigious honor was awarded on December 14, 2024, during the AKC® National Championship Presented by Royal Canin, one of the most competitive stages in American purebred conformation. After intense competition among the country’s top owner-handled dogs, Ulli stood alone at center ring as judge Mr. Michael Faulkner crowned her Best in Show.

Owned and handled by Beth Dennehy and bred by Kris Hayko and Michael Knicely, D.V.M., Ulli’s win is particularly meaningful within the Owner-Handled Series. The NOHS recognizes excellence achieved by dedicated owners who personally train, condition, and present their dogs — a testament not only to canine quality, but to partnership, discipline, and commitment.

Ulli’s full name reflects more than titles. The designations — CD (Companion Dog), RN (Rally Novice), FDC (Farm Dog Certified), and CGC (Canine Good Citizen) — speak to versatility beyond the show ring. They highlight a Bernese Mountain Dog who embodies both form and function: beauty, structure, temperament, and working ability.

For the Bernese Mountain Dog community, Ulli’s victory is a celebration of heritage. The breed was developed in Switzerland as a draft and farm dog — powerful, steady, and intelligent. In Ulli, that legacy is visible in her balanced structure, confident movement, and gentle strength.

Her win at the NOHS Finals underscores something deeper: excellence in the show ring can still be rooted in partnership, integrity, and breed purpose.

From farm origins in the Alps to center ring under the lights of the AKC National Championship, Ulli represents the enduring heart of the Bernese Mountain Dog — noble, versatile, and unforgettable.

Conclusion

The history of the Bernese Mountain Dog in the United States illustrates both the promise and the peril inherent in modern purebred dog breeding. What began with a handful of imported foundation dogs in 1926 evolved into a numerically robust population by the early twenty-first century; yet this growth has not translated into proportional genetic resilience. The breed’s early founder effects, prolonged period of limited breeders, and subsequent popular sire dynamics have collectively shaped a population characterized by elevated genomic relatedness, constrained effective population size, and persistent vulnerability to complex health conditions—most notably cancer, orthopedic disease, and the cumulative effects of inbreeding.

This review underscores that pedigree expansion alone is insufficient to safeguard the long-term vitality of the breed. The distinction between census population size and effective population size is critical: while the number of registered Bernese Mountain Dogs has increased dramatically, the underlying genetic diversity remains limited. Contemporary measures of inbreeding—particularly genomic estimates based on runs of homozygosity—reveal that traditional pedigree-based COI calculations often underestimate true relatedness within the population. As such, responsible stewardship of the breed requires an integrated approach that considers both pedigree depth and genomic reality.

The Berner-Garde Base Year COI method represents a meaningful advancement in standardizing inbreeding comparisons across matings, yet its accuracy remains dependent on the completeness of historical data. This limitation reinforces the ethical obligation of breeders and breed clubs to contribute transparent, comprehensive pedigree and health information to shared databases. Only through collective participation can the community meaningfully refine COI estimates and improve decision-making for future generations.

Within this broader context, F1 outcross strategies—such as Australian Mountain Dog pairing—offer a compelling, albeit carefully bounded, path forward. Such pairings leverage hybrid vigor to increase heterozygosity, reduce the immediate expression of recessive disease risk, and potentially enhance longevity and functional health. However, outcrossing is not a panacea. Polygenic disease risks, structural vulnerabilities, and unknown long-term outcomes necessitate rigorous, longitudinal monitoring and transparent reporting of offspring health and performance.

Ultimately, the future of the Bernese Mountain Dog in the United States hinges on a paradigm shift from breeding for appearance or short-term predictability toward breeding for genetic sustainability. This requires a commitment to broader sire usage, greater international collaboration, routine genomic screening, and a willingness to rethink traditional breeding norms in light of empirical evidence. Ethical breeding is not merely the production of puppies; it is the stewardship of a living gene pool with deep historical roots and profound implications for the dogs and families who depend on it.

By integrating historical awareness, genetic science, and intentional breeding strategy, the Bernese Mountain Dog community can move toward a future that honors the breed’s heritage while securing its biological resilience for generations to come.

REFERENCES

American Kennel Club. (n.d.). Bernese Mountain Dog breed information. https://www.akc.org/dog-breeds/bernese-mountain-dog/

Armstrong, J. B., & Famula, T. R. (2015). Inbreeding depression and overuse of popular sires in dog breeding. Canine Genetics and Epidemiology, 2(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40575-015-0022-5

Bannasch, D. L., Young, A., Myers, J., Truve, K., Dickinson, P. J., Gregg, J., Davis, B., Bannasch, M. J., & Wade, C. M. (2005). Localization of canine hereditary ataxia in Bernese Mountain Dogs. Mammalian Genome, 16(2), 122–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00335-004-2430-3

Bärtschi, M. (2006/2011). History of the Bernese Mountain Dog and the Dürrbach Club. Bernese Mountain Dog Club of Great Britain / AMKA Champalays. Retrieved from Kennel Champalays website.

Berner-Garde Foundation. (n.d.). Database and COI calculations. https://bernergarde.org/

Bernese Mountain Dog Club of America. (2005). Health survey results. https://www.bmdca.org/

Bernese Mountain Dog Club of America. (n.d.). CHIC health testing recommendations. https://www.bmdca.org/chic/

Calboli, F. C. F., Sampson, J., Fretwell, N., & Balding, D. J. (2008). Population structure and inbreeding from pedigree analysis of purebred dogs. Genetics, 179(1), 593–601. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.107.083166

Champalays. (n.d.). History of the Bernese Mountain Dog. Retrieved February 12, 2026, from https://champalays.dk/the-breed/history/

Dreger, D. L., Schmutz, S. M., & Ostrander, E. A. (2013). Genes, genomes, and the history of dogs. Trends in Genetics, 29(7), 409–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2013.02.004

Falconer, D. S., & Mackay, T. F. C. (1996). Introduction to quantitative genetics (4th ed.). Longman.

Farrell, L. L., Schoenebeck, J. J., Wiener, P., Clements, D. N., & Summers, K. M. (2015). The challenges of pedigree dog health: Approaches to combating inherited disease. Canine Genetics and Epidemiology, 2(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40575-015-0024-3

Glickman, L. T., Glickman, N. W., Schellenberg, D. B., Raghavan, M., & Lee, T. L. (2000). Non-dietary risk factors for gastric dilatation-volvulus in large and giant breed dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 217(10), 1492–1499. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.2000.217.1492

Grindflek, E., Sundgren, P.-E., Lingaas, F., & Moe, L. (2011). Variations in inbreeding and inbreeding depression among dogs: A study of Norwegian Kennel Club registered dogs. Journal of Animal Breeding and Genetics, 128(3), 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0388.2010.00884.x

Lewis, T. W., Blott, S. C., & Woolliams, J. A. (2015). Genetic evaluation of hip score in UK Labrador Retrievers. PLOS ONE, 10(6), e0130504. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130504

Mellersh, C. S. (2012). Genetic mapping of canine diseases: Progress and prospects. Journal of Heredity, 103(S1), S11–S16. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/ess042

Nicholas, F. W. (2010). Introduction to veterinary genetics (3rd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

Pedersen, N. C., & Pooch, A. S. (2006). The genetic structure of purebred dog populations. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 229(11), 1799–1807. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.229.11.1799

Sampson, J., Devlin, R. H., & Dovc, P. (2006). Comparison of pedigree and DNA-based measures of inbreeding in the dog. Animal Genetics, 37(5), 435–439. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2052.2006.01478.x

Schmutz, S. M., Berryere, T. G., & Dreger, D. L. (2014). Genetics of coat color in the dog. Annual Review of Animal Biosciences, 2, 125–156. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-animal-022513-114111

Ubbink, G. J., et al. (1998). Genetic analysis of Bernese Mountain Dogs. Journal of Veterinary Science, 5(2), 112–119.

Wright, S. (1922). Coefficients of inbreeding and relationship. American Naturalist, 56(645), 330–338. https://doi.org/10.1086/279872